- Home

- German Sadulaev

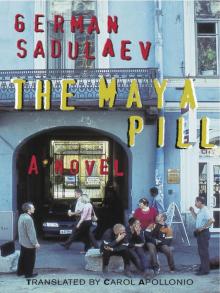

The Maya Pill

The Maya Pill Read online

The Maya Pill

German Sadulaev

Translated and with an afterword by

Carol Apollonio

Contents

PART I

Itil

CROSSROADS

FAMILY TREE

KHAZAR DEMOCRACY

RAVENS OF MORNING

HEGEMON

THE BOX

COLD CORPORATION

AT THE WAREHOUSE

ONE MILLION US DOLLARS

“GIVE ME TWO TABLETS”

BEAUTY WILL GRAZE THE WORLD

CHINA TRIP

THE TAO OF THE MID-LEVEL MANAGER

THE ROAD HOME

KNOCKING ON HEAVEN’S DOOR

FALLING STAR

PART II

Samandar

THE DUTCH VISITORS

DON’T GET SHAT ON

THE FALL OF KHAZARIA

WASTELAND

THE KURGANS OF STARAYA LADOGA

KHAGAN

THE CHINESE QUESTION

WHAT DO STRAWBERRIES HAVE TO DO WITH IT?

NACH DRACHTEN

SEX WITHOUT BORDERS

JASPER ROOT

LOVE, RUSSIAN STYLE

FOREIGN POLICY

PROSPECT OF ENLIGHTENMENT

PART III

Serkel

HAKAN

TRACES OF KHAZARIA

INAUGURATION

IT’S IN THE WATER

ESCAPE

PILLS AGAIN

PART IV

Poppies

INSOMNIA

THE SECRET OF FISH PASTE

LIFE AFTER DEATH

LIFE AFTER DEATH, CONTINUED

THE DARK TEREK

CONCLUSION

Atan khalam sarvatum*

In early spring of the year two thousand and XX from the birth of the prophet Jesus Christ—peace be unto him—I, Maximus Semipyatnitsky, have set pen to paper. My goal: to snatch humanity from the talons of Maya, of illusion.

I shall tell the whole truth, reveal hidden verities, openly proclaim treasured secrets. The fortunate among my readers will profit from the knowledge I reveal here and will find their pathway to freedom. The ignorant, though, will reject the path, the blind will pass it by, and the world will crumble and plunge down to hell—as well it should—but my conscience will be clear. I shall fulfill my duty before those who suffer, and in doing so bring benefit unto myself. At the preordained hour I shall soar aloft to higher worlds in an airplane made of flowers, having shaken off the things of the terrestrial earth, its flawed economic system and discriminatory social relations, like dust, from my feet.

O’men!

* The only inscription in the Khazar language that has been deciphered by scholars. Some linguists believe that it means “All things are possible.” The phrase was found inscribed on a stone stela that, some historians say, stood outside the home of a distinguished family of Khazar merchants; it may have served as their motto. Mainstream scholarship, however, does not recognize the stela, believing it to be a later fabrication; does not recognize the inscription itself, which is an imitation of the Sanskrit Devanagari alphabet; puts no stock in the belief that the inscription is in the Khazar language; and doesn’t think much of the translation either.

PART I

Itil

CROSSROADS

Bald Britney Spears writhed hysterically, slashed her veins, twisted her hospital bedding into a rope, and attempted to hang herself with it. Then she burst into tears, repented, summoned her former husband Kevin Federline, and promised to bear him a third child. Then she sobbed again, invoked the name of Beelzebub, called herself a fake, sought out the best tattoo artist in the United States of America, and had the number 666 branded onto the crown of her head.

Thirteen years ago, a scrawny old man materialized out of thin air in the bedroom of a pudgy girl. The old man looked like a goat and was wearing a baseball cap with “INY” on the front. The girl was clutching a curling iron in her hands, pretending it was a microphone, and gyrating in front of her mirror to the sounds of a Madonna tune coming from a cheap cassette player. The old man perched on the edge of a chair and with the muted and watery leer of a jaded pedophile observed the girl’s fleshy thighs bulging out from under her tight white shorts.

The girl glanced over and saw him, but before she could scream the old man reached over and handed her a bunch of pages torn from a school notebook. The pages were covered with elegant handwriting, with Gothic curlicues. The girl quickly skimmed the writing, then looked up at the old man, her big eyes brimming with greed and disbelief.

“What do you want me to do?” asked the girl.

She didn’t know Russian or Latin, or ancient Aramaic—only English, or, rather, American.

The old lecher would have understood her in any language, but he said:

“First just sign the contract.”

He could have answered in any language; he knows Russian, and Latin, and ancient Aramaic, and Greek, and Sanskrit. They say he even knows Albanian.

With the innate clumsiness of an overweight pre-teen, the girl lurched over to her school backpack, emptied its contents onto her bed, and fished out a ballpoint pen of Chinese manufacture.

The old man shook his head: “Blood. This kind of contract must be signed in blood.”

The girl was taken aback, but only for a moment. Staring impudently into the pervert’s eyes, she undid the button and zipper on her white shorts and lowered them to her knees. Then, hiking her gaudy stretch panties over to one side, she poked her finger between her legs and dug around inside. Without taking her eyes off the man’s face, she lifted her stained finger and smeared a crooked, rust-colored cross on the notebook paper with the ink of her first menstrual blood.

The old man gathered up the pages and vanished. Only then did the girl realize that his image hadn’t been reflected in the mirror.

The contract stipulated a thirteen-year term.

You might ask how I came to know these details. I learned them firsthand from one of the parties to the contract. And I’m not personally acquainted with Britney, so you can guess who I mean.

If you’ve read any books about voodoo or know anything about the history of the blues, you know the legend of the Trickster. Outside every city is a crooked crossroads, with a withered tree standing in its southwest corner. Every blues master has visited one of these corners on the night of a new moon. There he met the devil and sold him his soul in exchange for fame and glory. The devil in this particular legend is known as the Trickster, or Deceiver. No one can outwit him; he will steal your soul, dear child, and all you will get in return will be a pile of yellowed newspapers with your photograph on the front page.

The city of St. Petersburg has one of those crooked crossroads, in Vesyoly, at the place where Bloody Bolsheviks Prospect meets International Prostitute Kollontai Street. A withered old tree used to stand there, on the spot now occupied by a Neste gas station.

I used to be in a band with Ilya, who later made it big under the stage name “Devil.” We were coming back late from a rehearsal one dark night. Feeble little stars cowered behind a dirty gauze veil of clouds, and alcoholics, plagued with nightmares, tossed and turned on park benches nearby. The Trickster came coasting along in a burgundy-colored Volga, the deluxe model. He pulled up beside us just as we reached the crossroads, and invited us into his car. I immediately realized what was going on and instructed the old goat to kiss my ass. Mama taught me never to get into cars with suspicious-looking strangers.

But Ilya did. He got into the back seat and struck up a conversation with the old scumbag. Now Ilyukha sings his songs in huge stadiums and has his own TV show. Whereas my three solo albums came out in editions of twenty copies each, total, on c

assette.

Not too long ago, the old swindler visited me again. He told me about Britney, and a whole slew of other clients too. He had heard that I’d become a writer, and figuring that this might give him another chance, poked his contract under my nose. It reeked of urine from a railway station toilet.

My response to the Source of All Sin, after censoring out the nonstandard vocabulary, could be distilled down to two English words: get lost. Rebuffed, the tempter spat malevolently onto my kitchen floor, and his saliva sizzled and scorched a hole in the linoleum. It’s still there on the floor, under the cardboard carton that I use as a table for my electric teapot and toaster. You can come over and take a look: With its ragged edges and dark center, it resembles a black hole, like the ones in outer space, and gives off a sulfury smell.

The Adversary was in a pathetic state. He told me a sob story about how he’d been to see K, and P, had dropped in on N, and had even flown out to the middle of nowhere to see G, but everyone had turned him down in more or less insulting terms. The despondent seducer whined that now he would have to make a deal with a client you couldn’t even call a writer, a scribbling hack whose opuses even he couldn’t stand to look at, much less read, and that everyone in hell would mock him, the so-called Master of Evil, when he dragged that sorry-ass soul down there. O, how low he had fallen, after Goethe and Sorokin!

At that point the Prince of Darkness, drained of all hope, dissolved into a pale gray haze that looked like bus exhaust, and wafted southward in the direction of Moscow.

Literary critics had unanimously identified my latest novel as the most insignificant and forgettable book of the year. Most bookstores don’t carry it. Sales experts, following some tyrannical inner voice that they call “the dictates of the market”—though we know that the market has nothing to do with it—loaded the shelves with row upon row of copies of a single book by a different author, which had become a surprise bestseller. They even colonized the bookstore windows, piling up a million more copies in huge stacks that spill over onto the sills.

Verily, vanity of vanities, the things of this earth.

Thus did I twice shame the Enemy of the human race and save my eternal soul.

FAMILY TREE

My name is Maximus. Not Maxim, not Max, but Maximus; you can check my passport and driver’s license. I owe the name to my uncle, or rather, to his work buddies, who had marked some milestone in his employment by giving him an old book on the history of Ancient Rome just before I was born. Some random Roman emperor’s or general’s name came up, and my uncle, who was also my godfather, bestowed it upon me. Could have been worse. I’m eternally grateful to my godfather for not choosing one of those other names the Romans were so fond of, the ones that have both masculine and feminine equivalents in Russian. Like Valerian, Valentinian, Julius, or Claudius. It’s scary to think how many schoolmates I would have had to massacre during their tender childhood years for calling me girly names like Valka or Claudia behind my back.

My ancestors acquired the surname Semipyatnitsky during the years of serfdom. Don’t believe people with names like Sokolovsky, Tarasovsky, Dubovitsky, or Lebedinsky when they try to claim noble birth. On the contrary. That elegant “-sky” suffix usually marks the descendents of lowly peasants with no status whatsoever, who didn’t even know who their parents were, much less their ancestors, and accordingly were listed in the census under their master’s name: “Who do you boys belong to?” “We’re Colonel Ordyntsev’s chattel.”

What’s known for a fact is that my ancestor, the potent patriarch and founder of the family line, was a stableman on an estate in Saratov province, a carouser and cardsharp whose unreliable character had earned him the nickname Seven Fridays—for him, every day was the beginning of the weekend. It’s also known that my ancestors weren’t Russian, and might have been of Tatar blood. My father’s name is Raul Emilievich. So my full name is Maximus Raulevich Semipyatnitsky. No one uses my patronymic, though; as is said in such cases, I have not earned it.

Our distant relatives bear the name Saifiddulin. Raul and Émile are French names, as far as I can tell, but though it might seem strange to you, they’re extremely popular among Russian Tatars. This supports my family’s hypothesis about the Tatar blood.

But there’s another story as well, a beautiful legend. Through the ages, generations of Semipyatnitskys have passed down the tale that our family originated not in a Tatar tribe—though my forefathers must have come into close contact with Tatars as a matter of course, as neighbors in the Turkish world—but rather in ancient Khazaria, which at one time was a great power, and which vanished, like Atlantis, in the currents of history. It’s even said that our family was related to the Great Khagan.

I don’t know how much of this legend is true and how much of it is just inspiring nonsense that my ancestors made up to boost their morale in their demeaning and dependent social position. But whether there’s some kind of genetic memory at work, or whether all these tall tales have just seeped into my subconscious, for whatever reason, I’m sometimes visited by strange dreams. Last night, for example.

KHAZAR DEMOCRACY

Once upon a time, in the glorious city of Itil, which stands on the River Volga, in the capital city of the Khazar Tsar-Khagan, there lived a herdsman of horses, the younger son of a man named Nattukh, Saat by name. This is no epic tale; there was nothing heroic about Saat; he was just an ordinary man living an ordinary life. He pastured his mares on the steppe, carried foals in his arms, shoveled manure, and hauled it from the corrals. Of course a poor herdsman like Saat wouldn’t live in Itil itself; a square sazhen of land an arrow’s flight from the Khagan’s palace cost way more than he could afford: five weights of silver. No, he lived far away, at the very edge of the steppe. And that is as it should be: Where can you find space to graze your mares in Itil? Half the time you can’t even find an open hitching post. Horsemen wander the streets, searching among the stone houses, but the posts are all being used, there’s not a single free one to toss your reins over! The steppe, though, is a land of plenty: feather grass and wind. Saat’s tent was tattered, draughty, and full of holes. But he did not lose spirit. On a summer night, the stars would shine their way through the rips in his tent roof; their rays caressed and warmed him.

But Saat had no one, only starlight, to caress and warm him. He was lonely. He did not crave gold or silver; it wasn’t a big stone mansion he wanted, not glory and fame; his only desire was to have a black-haired maiden by his side, a girl with hazel eyes, a bosom like a young mare’s udder, and gentle sloping withers. Long did he crave a wife!

But then that desire, too, passed.

And after that Saat had the perfect life.

Itil held no appeal for Saat; Saat forgot Itil. Even the tax collector forsook the path to Saat’s tent. When a man lacks a wife and worldly wealth, when he doesn’t go to the bazaar or to the bathhouse to gossip; when he doesn’t inhale the dust at the Khagan’s gate, it is as though he doesn’t exist; he is invisible. And free.

Sometimes Saat would think: Great is the Khagan, glory to him and victory over all his foes, what use to him is a poor herdsman and his mares? How can the Khagan, blessed be his name under the moon and sun, be mindful of all the herdsmen in the boundless steppe? Send troops into battle, gather in the taxes, array concubines on thick woolen carpets, manage the affairs of state! And the herdsman, for his part, what need has he of the Khagan? The bay mare has foaled, the milk in the burdiuk has fermented wrong and turned all clotty, and yesterday the wolves howled all night long, what if they attack the horses? The Khagan and the herdsman lead separate lives. And so be it.

But every year there was a marvelous and strange occurrence. On the second moonless night after the day when light and dark fell in equal measure upon the spring grass, Saat would rise with the dawn; he wasn’t quite awake, but sort of still sleeping, sleepwalking. He would take up his kizil-wood staff and set forth in the fog, in the direction of Itil.

If he

had been able to see, he would have realized that he was not alone. From all over the steppe, men walked, swaying blankly from side to side in their tattered beshmets. Eyes open, but dreaming. Falling down, bumping into, or even trampling one another. But pressing inexorably forward, onward, like a swarm of ants crossing a ford.

For once a year all of Khazaria is called upon to vow for the Khagan and to elect the Great Kurultai.

So here comes Saat, making his way across the steppe, and his head feeling like a buzzing beehive, but divided into different chambers, each swarming with its own political party, so not just one beehive, politically speaking, but several . . . peehives, if you will. And even if you won’t.

So Saat feels that three tenths of his head, from the right ear to the crown, are for United Khazaria: this peehive is the biggest and the Khagan himself is in it or nearby. And Saat feels that two tenths of his head, the crown and half the back, are for A Just Khazaria, which is new, and also for the Khagan, but from the other side, as it were. And one tenth of his head, the part by the left ear, is for the Utmost Primordial Communal Peehive Party of Khazaria. This peehive is ancient; it has come down from his forefathers. And one half tenth of his head, behind the ear, just a scratch, really, is for the Robber Bandit Peehive of Khazaria. And this party has no more sense than a pile of rotten straw, but its leader is a bandit they call the Thrush, Solovey, and he’s a riot, so much fun! The rest of his head stayed home; it didn’t go to vow anything, didn’t elect anyone. And fine, so let half an ear come, that should be enough for the Great Kurultai.

Shamans lead a bear around the streets of Itil. The bear jingles its bell, dances. United Khazaria is the winner. Who else is there anyway? It’s all just Murzlas in the Kurultai. They’re not like Khazars: dark-skinned, curly-haired, with round eyes. There’s a saying in the bathhouses: For the Murzlas the Khagan is no law, and the shaitan spirit no brother. Though the shaitan may very well be their father. But you hear all kinds of things in the bathhouse.

The Maya Pill

The Maya Pill