- Home

- German Sadulaev

The Maya Pill Page 2

The Maya Pill Read online

Page 2

Saat returns at night, collapses in his ragged tent, sinks into a deep slumber. Gets up the next day and remembers nothing! Feet all bloody, but where he has been and what he has been doing?—might as well ask the wind!

The old women whisper that every year the Itil sorcerers and shamans send out a huge cloud of foul air, filled with violet-colored dust, gathering the entire Khazar people together to vow allegiance. The ragged herdsmen come to Itil, trudging on their last legs like the living dead, and they speak their vows, vote in swarms with their voices. Afterward they have no recollection of whom they voted for, or of even voting at all. But the Khagan is eternal, and the Kurultai is with him: you swore allegiance back then, so now obey; go forth: raid, gather taxes for our coffers and maidens for our beds, bow down to the earth before us. For we are blood of your blood, flesh of your flesh and it’s all for your sake. And the Khazars live on. They carry on as they can, in their own way. And the Khagan, too, with the Kurultai. Until next spring. This is one way. And it is even a good way. Just so long as there’s no war.

RAVENS OF MORNING

Every morning around eight thirty I venture forth. The door to the apartment building closes lazily behind me on its pneumatic hinge. The first thing I hear is the croaking of ravens. They’re everywhere; they live here year ‘round. They weave their black-branched nests on the treetops in the courtyard, and subsist on a diet of human leavings gleaned from the trash bins.

Sometimes I ask myself: Why is it only the most disgusting, ugly, and nasty creatures that have adapted to live with human beings? Ravens, rats, and cockroaches are man’s constant companions in his wanderings through time. They establish their abodes either inside those of humans, or in close proximity to them. For whatever reason, human cities are devoid of proud eagles, noble deer, gorgeous butterflies, and even soft-furred beavers. Could it be that in the Creator’s plan these fauna are placed near us so as to enhance the aesthetic effect of man’s perfection, by contrast?

Or do they sense that we’re kindred spirits, grimy, low birds of a feather?

The ravens croak in the morning. Harken to where the noise is coming from. If it’s from the right, no problem. But if a raven croaks three times on your left, no good will come of it. An ancient Khazar omen.

Observe also the position of the waxing moon. If it’s on the right, all is well; on the left, you’re in trouble.

If you see a bad omen, though, all is not lost; there’s a sure way to protect yourself. Immediately spit three times over your left shoulder. Everyone knows that the devil lurks behind a man’s left shoulder; there’s an angel on the other side. So spit three times into the devil’s snout; that’ll throw him off. Then make four complete turns clockwise, that is, left to right. That’ll make the devil dizzy, and then the angel can give him one in the rear. Last, take off your coat, turn it inside out, and put it back on. It will utterly baffle the demon. And he won’t give you any more trouble.

I learned this from my Khazar grandma. She also taught me how to cast spells using a dried branch, how to undo an evil spell using nothing but water, how to draw signs to protect yourself from shape-shifters, and how to distinguish the living dead from the living living, and the living dead from the dead dead.

But I’ve forgotten just about everything from that distant time, those years when I was a schoolboy, and used to spend my summer vacations on a farm far away, on the shores of a broad, muddy river, with my wise, fairy-tale grandmother. It was so long ago, it feels like another lifetime. Or someone else’s.

The past, all that used to be, was burned long ago.

It wasn’t our life, it was all just a show.

A line from one of those three cassette albums.

The life I live now is completely different.

HEGEMON

I greet the ravens, and if necessary, I spit the shoulder demon away, and head for the shopping-center parking lot. I go up to my boxy gray car, get the remote key out of my pocket, and press the button. The door locks click, and I open the driver’s side door and crawl in.

My car is a 2006 Renault Logan, ultra-economy class, designed for the Turkish market and assembled in Moldova or someplace. Bought on credit with a three-year loan with an insane interest rate. Of course the color caused no end of torment. When the bank agreed to the loan, there was too much variety on the lot: For example, instead of drab gray, you could also choose plain gray. Or drabber gray. And then, there was also plain drab gray. Well, I put a lot of thought into it and finally decided I might as well get a gray one—I liked the color so much.

We could spend some time on this. These days, a man’s social status, his identity and place in the world, everything that he has (or has not) achieved in his lifetime, can be gauged quickly and easily with one look at the car he drives.

In one of my previous lives, sometime around 1995, I was walking along the Palace Embankment past the Admiralty one warm summer night, hand in hand with a tall, ravishing brunette, talking big: “Katya, if today, right this minute, the devil came up and let me see into the future, and if I saw that I was destined to become an ordinary man like millions of others, that I would just go to work every day, come home at night and watch TV, spend my weekends shopping, and all the rest of it, and if the devil were to hand me a gun, I would shoot myself right then and there, without a moment’s hesitation!”

Over the next couple of years Katya got tired of me, of my tendency to disappear into a black hole for weeks and months on end and then suddenly turn up with no warning, “Hey, you busy tonight?” Katya married a good man. Katya has a job as a senior legal advisor, an assistant prosecutor. She might even have made prosecutor by now.

And here I am getting into my cheap Franco-Turkish car, thinking what a dirty trick it had been for the devil not to show up then and there with that movie about my future life and a loaded pistol in his clawlike hand. But what can you expect from the spawn of hell? Now he can gloat at the sight of me, the man I’ve become, a fate worse than death, the very man I swore I’d never be. On the other hand, don’t forget, I did turn him down twice when he offered his contract—my soul in exchange for a chance at something more. Gloating is all he has.

Yes, I careened across the globe from the White Sea to the Indian Ocean and back again; tried on a monk’s cassock, then ragged blue jeans; walked around clutching a string of wooden prayer beads, then the handle of a Makarov pistol. I scrambled the best, formative years of my life in the geometric Brownian motion of an unfathomable fate. Now what’s left of me spends its days in voluntary servitude as an ordinary office drudge, a cheap white-collar worker in an off-the-rack business suit, my double chin spilling over the necktie leash around my fleshy neck.

I’ve merged into a class totally devoid of class consciousness. I’ve become what is demeaningly designated as “lower middle class,” the baseline standard for poor taste and ineptitude, unenvied even by blue-collar workers, who merely detest us for getting to work in warm, dry offices, while manual workers spend their days up to their ears in shit and engine oil, poking around in the guts of broken machines. No, they don’t envy us; sometimes they actually earn more than we do. Successful people, the upper middle class, hold us in contempt, whereas for high society we don’t even exist at all except as an anonymous throng of pathetic losers, barely visible behind the wheels of the junk cluttering up the road and getting in the way of their limousines and sports cars.

In songs and jokes we’re “mid-level managers,” MLM for short. The term is not to be taken literally; it implies that there are other managers on an even lower rung, but there’s actually no one below us; the next level down is the flames of hell. So when you think about it, we managers don’t really manage anyone—there’s no one there. But “manage” has another meaning as well: to control. In the strictest sense of the word, we’re not really managing—but in fact we sit at the controls of the entire global economy.

I shall now speak out on behalf of the insulted and injured, the prole

tariat of our new epoch. Lend me your ears!

In stuffy, crowded, overstaffed offices from San Francisco to Qingdao, decrepit air conditioners rattle noisily in the background, or worse, there’s no AC at all. Amid the din and shouting, with Windows on the verge of collapse, the MLM presides. A telephone receiver is permanently attached to his ear, and he himself is plugged into the computer network like a mere appendix to the keyboard. There he sits, building the economy, hastening the march of progress, propelling mankind inexorably onward toward its inevitable collapse.

Not stockholders, who care only about their dividends, not the masters of business standing regally over the fray like Kutuzov and Napoleon at Borodino, themselves subject to the flow of history and lacking free will; not the top managers who claw bonuses for themselves out of each and every deal and preen before fitness-club mirrors; and certainly not the actual workers in the factories, who could give a shit about any of that—no, it’s the office worker: the manager of sales, procurement, logistics, export, import, marketing, human resources, and whatever the hell else—it is he who determines the fate of the world, he, the very embodiment of efficiency, who implements the laws of economics.

An exhausted and alienated import manager in France compares pricing and supply proposals and selects some product from China after rejecting an Italian company’s bid. Meanwhile his director flies to Rome on company money, stays in a Radisson or Hilton, drinks himself under the table at some banquet in an Italian restaurant, and seduces the host’s wife, and now he needs to get a contract with the Italian company, if only to justify his own existence and his exorbitant salary. The exhausted and alienated import manager couldn’t care less; it makes no impression on him, even when he finds out that it was the director of the Italian company who delivered his own wife to the drunken French director’s bed (and she’s not his wife anyway, but an “export escort” hired especially to seal the deal). All the import manager did was compare prices and terms and select the Chinese product.

If the director digs in his heels, the import manager won’t argue, he’ll give in. He has a secret weapon: covert sabotage. Almost immediately things start to go wrong with the Italians. Deliveries are delayed; the paperwork is mixed up, work at the plant grinds to a halt, and the entire transaction comes up a loss. The director gets taken down a peg at the next stockholders’ meeting, and deliveries begin coming in from China.

Because that’s what made sense from the beginning. And the exhausted and alienated manager, who doesn’t stand to gain or earn bonuses from any of these deals, all he wants is for everything to balance out, to make sense, and to benefit the business. It gives him a feeling of functional harmony and insulates him from an awareness of the absurdity of existence.

That’s all.

Thousands upon thousands of import managers the world over make the same kinds of decisions, and terrestrial exports soar to celestial heights.

When he’s done with the world economy, having finally directed it into the proper channels and calculated all the trends and vectors, the exhausted manager sets off for home.

And immediately starts in on the economy from the other side.

He buys up mass-market clothing, fills the seats in chain restaurants, clears stuff off the supermarket shelves. It’s not easy; he can’t cram everything in, but he keeps on trying: eating and drinking, drinking and eating. Periodically he stuffs some new, pointless item of clothing into the one miniscule closet that itself takes up nearly all the space in his apartment. And who, if not he, can consume all that stuff coming out of the world’s factories? He’s tired, he’s miserable, but he knows how to laugh, he seeks out entertainment, and after all, who, if not he, will fill the dance clubs and concert halls? Occasionally he’ll even buy a book and read it, a bestseller, just to keep up with things, to follow what’s going on up there in first class. It was written for him, after all; and he’s the one drenched in the toxic spit of their scorn: Yes, I’m a piece of shit, a loser, he agrees, and keeps on reading. Who knows, he might hit the lotto jackpot and wind up in the penthouse of the Tower of Babel, and, if so, he’ll be able to take advantage of what his reading has taught him about the difference between a genuine thirty-five thousand-euro watch and the one that’s not so genuine, the kind that your basic dimwit can pick up for fifteen hundred American dollars.

He believes in God, believes in the President, believes in the Law, believes in the Market, believes in Science, Santa Claus, and the Tooth Fairy. He takes out loans for his condo and his car, he maxes out his credit card for a serving of yogurt. It’s his way of issuing credit to the economy, a bond of trust to the government and to society as a whole.

The most deranged among them even bring children into the world.

He is an optimist.

He is Hegemon, he is mankind in the twenty-first century.

Respect this man, bland and faceless though he may be.

Rejoice in his blandness. For when he becomes aware of his true class interests, he will turn the world upside down, without even reaching for a weapon. Everything is already in his power. And if this million-handed mid-level manager should collectively decide to press the delete key, he will erase the Universe.

THE BOX

Now this is how the story goes:

That day I pulled up to the office as usual in my gray Renault with its funny-looking, stunted little hood, and wedged the car into an improvised parking place on the lawn in front of the building. I got the lanyard with the Smart Card out of my pocket and draped it around my neck. This is my personal collar, the visible mark of my servitude. Nine-to-five slavery, they call it in the advanced capitalist countries, where over the course of their many decades at the reins of power the liberal socialist parties have trained employers (i.e., exploiters) to observe the eight-hour working day (including lunch break). In my case that comes to nine-to-six; here in the former land of triumphant socialism those eight hours do not include your lunch break.

The sensor reads my Smart Card and records the times of my arrival in the morning, my departure at the end of the day, my lunch and restroom breaks, and my other personal time, which must not exceed one half hour per day, total. There are fines for tardiness, for leaving work early, and for exceeding the allotted break time.

I passed through the turnstile, swiped the heavy metal door open with my Smart Card, and walked past the secretaries’ desks to the Import Department. My desk is next to the door, so people are coming and going behind my back all day long.

Could be worse. This girl I know works in marketing for an office furniture company. Her desk is right in the middle of the showroom. It has a price tag on it. So while she’s sitting there doing her work, customers keep coming up to her desk and opening and closing the drawers, peering underneath and feeling the legs (of the table), and knocking on the desk with everything but their teeth to test the quality of the veneer. She says that she’s gotten used to it and doesn’t even notice them anymore.

The Import Department is a medium-sized rectangular room with a windowless interior wall; a glass partition separating Import from IT; a partition between the Department and the corridor; and the building’s external wall, which has three windows (no AC). There are twenty-four other desks with twenty-four employees (besides me) working at them. The desks are jammed right up next to each other, with narrow aisles leading to the printers, the fax machine, and the copier. Pretty near constantly, all twenty-four employees are yelling into their phones, competing with one another to be heard. A couple of hours into the workday, my head starts to throb from the racket; by lunchtime the oxygen in the room is depleted and we’ve switched over to a carbon-dioxide diet, like plants. We haven’t yet mastered the art of photosynthesis, though, so what we’re exhaling is not oxygen, but the same gas we’re breathing in, only more concentrated. The windows are open year-round, but that doesn’t help: The dense, stifling atmosphere in the room blocks any fresh airflow; if you put a candle on the windowsill, the flame woul

d stand utterly still and vertical, without the slightest movement, like the consciousness of a yogi in a profound meditative state. If fresh air somehow manages to break through, the draughts infect one third of the office population with a whole smorgasbord of upper-respiratory ailments.

My job title is Leading Specialist. That’s a great jumping-off place for a career if you’re twenty-five. For a man of thirty-five it’s the kiss of death, a complete dead end.

I am thirty-five.

That morning I thought about it again, and my soul felt like . . . like a herd of scratching cats. Or, rather, it was more like if the cats had spewed their liquid and solid excrement directly into my soul, and the scratching I felt was them trying to clean up after themselves. Have you ever seen a cat scratching at the linoleum after he’s peed on it, imagining that he’s covering the evidence?

I tossed my faux-leather briefcase onto my desk, on top of a heap of random papers, sank onto my chair, and, forming the classic Anglo-American fuck-you gesture, jabbed the computer’s ON button with my middle finger. It started booting up, and the monitor went white. The face of Jessica Simpson flashed briefly before me (the intermediary desktop graphic I’d installed)—but then the screen showed the standard corporate interface for my workplace, that is, the Cold Plus Corporation.

First thing, I clicked on the bat image to check my e-mail. Everyone else in the department uses Windows Outlook; I’m the only one with The Bat. An involuntary extravagance. The IT People simply forgot to switch my e-mail program over when they installed the office system. I like The Bat.

The computer is full of bats.*

The program reminds me of Grebenshikov’s song about the Yellow Moon. It also makes me think of vampires and Pelevin’s Empire V. But the real advantage is that when you forward letters from contractors to colleagues, they arrive as though they were sent directly from the original sender—no middleman—so you don’t have to deal with the fallout.

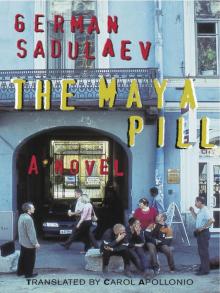

The Maya Pill

The Maya Pill